The Silent Struggle: How Trauma Affects Early Literacy Development

As a school psychologist, I've had the privilege of working with countless young children, and I've seen firsthand the incredible resilience they possess. However, I've also come to understand a critical, and often unseen, factor that can deeply impact their learning: trauma. When we think of trauma, we often imagine a singular, dramatic event. But from a psychological perspective, trauma can also stem from chronic stress, neglect, or exposure to violence. These experiences, especially during the formative preschool years, can have a profound and lasting effect on a child's brain development, directly influencing their ability to acquire the foundational skills for reading and writing.

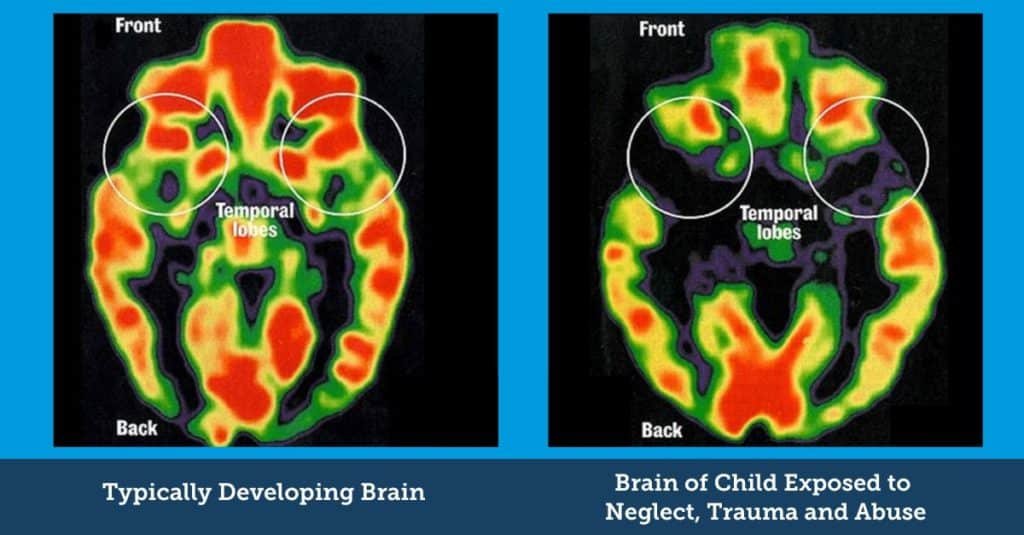

The Neurobiology of Trauma and Its Link to Literacy

Research shows that the brain of a young child is incredibly malleable, or "plastic," making it highly susceptible to the effects of trauma. A child experiencing chronic stress lives in a constant state of fight-or-flight. This state, driven by the overactivation of the body’s stress response system, can lead to a sustained increase in stress hormones like cortisol. According to the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, this can disrupt the development of key brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus (NCTSN). The prefrontal cortex is responsible for executive functions like attention, working memory, and impulse control—skills that are absolutely essential for a child to follow multi-step instructions, sound out words, and hold a sentence in their mind. Similarly, the hippocampus, which plays a crucial role in memory and learning, can be affected, making it difficult for a child to retain new vocabulary or recognize letter-sound correspondence.

Image Source: Dr. H. T. Chugani, Newsweek, Spring/Summer 1997 Special Edition: “Your Child: From Birth to Three”, pp 30-31

The impact of this neurological disruption is not just theoretical; it manifests in the classroom in very real ways. A child might struggle to focus during story time, exhibit difficulty with phonological awareness, or have a harder time with vocabulary acquisition because their brain is prioritizing survival over learning. The cognitive and emotional resources they need for literacy development are instead being used to manage their internal stress, leaving little room for academic engagement. A study published in the Journal of School Violence found a direct correlation between early exposure to violence and lower reading achievement in elementary school students (Duplechain, Reigner, & Packard 2008). This research highlights that the struggles we see in a child's academic performance are often a symptom of an underlying issue, not a lack of effort or intelligence. It's a silent struggle that requires our empathy and a new approach to education.

Creating a Trauma-Informed Literacy Environment

Understanding this connection is the first step, but what can we as educators and parents do about it? The answer lies in creating a trauma-informed environment that prioritizes safety, stability, and strong relationships. Research shows that a positive teacher-student relationship is a powerful protective factor for a child who has experienced trauma (National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative). With this foundation, we can implement several practical strategies to support early learners.

We can begin by establishing predictable routines. Trauma can make a child's world feel chaotic and unpredictable, so consistent daily schedules, clear expectations, and visual timetables create a sense of safety and control. This helps a child's nervous system calm down and become more receptive to learning, allowing their brain to shift from a state of hypervigilance to one of curiosity. Building on this, we must embrace social-emotional learning (SEL). Before we can expect a child to read, they need to be able to regulate their emotions. Incorporating activities that teach emotional literacy—like identifying feelings or practicing mindfulness—can build the self-regulation skills they need to engage with academic tasks. This proactive approach helps them develop the internal tools to navigate stress and focus on learning.

Furthermore, we can provide a "safe space." Designate a quiet corner with soft pillows, calming objects, or noise-canceling headphones where a child can go when they feel overwhelmed. This gives them an outlet to de-escalate without disrupting the entire class and reinforces the idea that their feelings are valid and manageable. This is not a punishment but a tool for self-regulation. Finally, we can use storytelling as a bridge. Reading stories that feature characters who overcome challenges can be a powerful way for children to process their own experiences without having to talk about them directly. It's a non-threatening way to build empathy, resilience, and a sense of hope. These narratives can also serve as a way to build a shared vocabulary around emotions and problem-solving, making it easier for children to express their feelings when they are ready.

In my work, I've found that these strategies are not just for children with known trauma; they are good for all children. As a study from the National Education Association points out, "trauma-informed practices can help educators collaborate to support student mental and physical health" and "foster a positive school climate where students feel safe and confident" (NEA). By creating an environment that is sensitive to the lingering effects of trauma, we're not only helping our most vulnerable students heal but also building a stronger, more supportive foundation for everyone to thrive. It’s about creating a space where every child is seen, safe, and ready to learn.

Works Cited

Duplechain, Rebecca, Jennifer Reigner, and Michael Packard. "Violence Exposure and Reading Achievement in Elementary Students." Journal of School Violence, vol. 7, no. 4, 2008, pp. 1-18.

Dr. H. T. Chugani, Newsweek, Spring/Summer 1997 Special Edition: “Your Child: From Birth to Three”, pp 30-31

National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative. "Creating a Safe and Supportive Classroom Environment." U.S. Department of Education, 2021.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). "Complex Trauma: Facts for Educators." NCTSN, 2022.

National Education Association (NEA). "Trauma-Informed Practices." NEA, 2023.